Thursday, August 29, 2024

The Battle of Largs and its aftermath

Not surprisingly, all attempts at consolidating Scotland crashed to a halt, and the minority of King Alexander was as tumultuous as such usually are. Eventually, the young king reached his majority and threw off the rule of constant squabbling regents some of whom had gone so far as to kidnap him and his queen.

In 1263, the 22-year-old king determined to finish the job his father had started. He began negotiations by laying claim before Norway's King Haakon IV of Norway to the Hebredes and all the lands of mainland Scotland. The Norse king rejected the claim and the Scots invaded Skye to take it. Haakon gathered a large fleet believed to be as many as 200 longboats to invade Scotland, planning to take back western Scotland and firm their claim to the isles. Generally a longboat carried about 40 men, so this was a formidble invasion force, numbering in the thousands. King Alexander cannily sent friars as envoys possibly to try to reach an accord but more likely to merely delay the invasion while he gathered his own forces. Whichever the original intent, the invasion was delayed. When negotiations broke down, the Norse struck, first one arm of the fleet ravaging all around Loch Lomond, buring, killing and pillaging. That arm rejoined the main force. At Cumbraes, King Haakon poised to invade the mainland of Scotland.

The Scottish force had gathered in Ayr Castle under the leadership of the redoubtable Alexander Stewart of Dundonald, a crusader who brought the experience the young untried king needed. They gathered mainly mounted knights and men-at-arms supplimented by local foot infintry, armed with axes and bows. The negotiations had delayed the attack until autumn, but it is unlikely that the Scots counted on the Norse being battered by a storm. That was likely more luck than good planning, since even in autumn storms are not constant.

Either way, as the tremendous Norse fleet neared the coast a short distance north of Ayr, a storm hit. The Norse fleet was badly battered loosing several ships and the men they carried. But the fleet was still mostly intact and made landfall at Largs, possibly intending merely to repair their damaged ships. King Haakon came ashore and divided his force, with about 800 on the beach commanded by King Haakon, guarding their ships and a smaller division of 200 men commanded by Ogmond Crouchdance on a nearby mound.

Word was quickly carried to the Scottish leaders some 40 miles away. There is no record if King Alexander was with the army. I believe he must have been because he had reason to want to prove himself to his people, but there is no doubt that the actual commander was Stewart of Dundonald. They led their army north to defend the kingdom.

At the sight of the attacking Scots, Ogmond realised he was seriously outnubmered and feared he and his men would be cut off from the main Norse force, so he began an orderly retreat. The Scots met the retreat with a fierce charge that turned it into a chaotic route, many, perhaps even most, were slain as they ran. Seeing the slaughter going on, King Haakon ordered his men to retreat to the ships. In savage fighting, many Norse were slain as they fell back but the ships were effective makeshift fortresses. The Scots then pulled back to the mound from with the Norse had retreated.

The Norse made one last sortie and succeeded in pushing the Scots back from the mound. As night fell, there was no clear winner, but the Norse invasion had turned into a disaster. The next morning the Scots held back allowing the Norse to gather their dead and retreat. Although the results are referred to as inconclusive, there is no question that King Haakon retreated with a battered army no longer capable of invading Scotland. The right of the kingdom of Scotland to all of the mainland of Scotland was no longer in question and with King Haakon's death in Orkney, negotiations for transfer of the Hebredes to the kingdom of Scotland were renewed.

Thanks to the Battle of Largs and its aftermath by 1266 the map of Scotland for the first time would be very recognizable by any Scot. A strong and successful King Alexander III was in firm control of his own kingdom and the Scots free of the fear of invasion from the north.

Tuesday, July 9, 2024

How important was the Battle of Bannockburn?

It was a valiant fight against overwhelming odds and few Scots can think of it without pride. King Robert surprised as he surveyed the battlefield by Sir Henry de Bohun and killing him with a single blow of his axe in single combat. Earl Thomas Randolph reproached by the king for having let 'a rose fall from his chaplet' and rushing to cut off the English attempt to reach Stirling, winning the first fight of the battle. It is hard to think of any battle with a more stirring story.

|

| King Robert in single combat with Sir Henry de Bohun |

In one way, of course, the Battle of Bannockburn was vitally important. It proved to Scots that they could defeat the English. In a way the many smaller skirmishes and attacks on English held castles had not proven that. The devastation to pride and self-respect was redeemed by an overwhelming victory, but what else did Bannockburn give Scotland?

It returned the Scottish prisoners who had suffered immensely at the hands of the English. Gallant Bishop Wishart came home, blind but still one of Scotland's greatest patriots, as did Christine de Brus who would later hold Kildrummy Castle against an English army untl her husband defeated them in the battle of Culblean, turning the tide of the Second War of Scottish Independence. It returned King Robert's wife and his daughter who would be the mother of the Stewart line of Kings, so their importance cannot be overlooked.

One of the results was the profit from the spoils of the battle and the ransoms. Thousands of men took a share of the spoils home with them to help rebuild the kingdom that had been despoiled and the government took a large share of the spoils and received some vast ransoms to continue the fight.

As nation building, it was vital. As a battle, it had no real results other than the surrender of Stirling Castle because it did not do is end the war. I have seen mistaken comments such as that "It allowed Robert the Bruce to secure Scottish independence" which is simply not true. Neither England nor the Pope recognized Scottish independence until fourteen years later, years spent in constant warfare.

I think that makes it less important as a battle than many people believe. So in the next few weeks I am going to write about the lesser known battles which were essential to Scotland's development and survival.

Saturday, March 16, 2024

Were Robert the Bruce and his captains fighting for freedom?

Someone recently put it to me that Robert the Bruce and his captains were fighting for power, not for freedom. He commented that it was just something that Gibson put in Braveheart. Considering that Gibson got almost nothing right about William Wallace, Robert the Bruce, or the start of the Wars of Scottish Independence, I can understand that skepticism. Certainly, William Wallace did not go around screaming "Freedom!" while wearing blue face paint. But is it just possible that they were fighting for freedom? And if so, what did they mean by 'freedom'? (For that matter, what do we mean by it?)

Well there were certainly mentions of freedom in the writings of the time. The first I am aware of was in the Declaration of Arbroath written in 1320. The word is part of the most famous paragraph of that historic letter, written to Pope John XXII and signed by eight earls and forty barons. It made a profound argument for the recognition of Scotland's independence from English rule and Robert the Bruce as Scotland's lawful king.

It was written in Church Latin, as one would expect in a document to be presented to the pope, and contained one of the most quoted sentences in Scotland's history.

Non enim propter gloriam, diuicias aut honores pugnamus set propter libertatem solummodo quam Nemo bonus nisi simul cum vita amittit.

Translated into English, it reads: It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom, for that alone which no honest man gives up but with life itself.

There are other 14th century references to freedom.

Freedom is mentioned a number of times in the iconic narrative poem The Brus written by Johne Barbour in 1370 about four decades after King Roberts' death, when some of his followers were still alive and had spoken with Barbour, as he actually mentions in the poem. One of the best known references from Barbour's work is on a plaque over where the king's heart is buried in Melrose Abbey. The plaque entwines a carving of a heart (which you also see on the Douglas coat of arms) with a Saltire, Scotland's national flag.

In the original Early Scots it reads: "A noble hart may have no ease, gif freedom failye."

Translated, this reads: "A noble heart shall have no ease if freedom fails."

However, that is only one line of Johne Barbour's paean to freedom.

Because of its length I will only include my own translation into English, but you can find it in the original Early Scots here.

Ah! Freedom is a noble thing.

Freedom gives man happiness,

Freedom all solace to man gives.

He lives at ease who freely lives.

A noble heart may have no ease,

Nor nought that may him please,

If freedom fail; for freedom to please oneself

Is loved above all other things.

No, he who has ever lived free

Can not well perceive the nature,

The affliction, no, the miserable woe

That is coupled to foul servitude.

But if he had put it to the proof

Then he would learn it all by heart,

And would think freedom more to prize

Than all the gold in the world there is.

(This translation is my own work, so any errors are totally on me. If you believe you have a correction, please let me know.)

Thus, Barbour expressed pretty clearly what he thought freedom was, at least in part, the ability to please oneself or do as one pleases, although he certainly also believed in duty to lord and monarch. Probably like most of us who have duty to family and bosses as well as nations to which we are loyal, he and other medieval Scots had a somewhat confused definition of the word. But whatever they believed it was, freedom was a concept many must have fought and died for.

Saturday, March 2, 2024

The Bonnie Earl o' Moray

I suppose that most of you are acquainted with this ballad. It is worth a look not only because it is a lovely ballad, a very old one at that, but also because it is based on a fascinating historical event.

For anyone who does not recall this song, here is my favorite performance by Old Blind Dogs.

The bonnie Earl o' Moray (yes, it is pronounced like Murray but is not the same thing 😜) was James Stewart, Lord of Doune and 2nd Earl of Moray in that creation, a direct descendant of King Robert the Bruce and distant cousin of the current King of Scots, James VI. As was so often the case in the midst of the Reformation, politics were complicated and too very often bloody. They were when another Stewart, the illegitimate son of King James V and a fervent Protestant and former regent for James VI, was assassinated in 1570 in the street by a carbine shot from a window - possibly the first political assassination by gunfire.

King James gifted young James with wardship of the deceased earl's two daughters and the right to marry one of them. (Are you getting confused by all the Jameses? Have pity on a poor author who has to deal with all the men in a historical novel having the same first name.) This set off some criticism because the Lords of Doune were much lower in status than the earls of Moray. It certainly indicates that he was on good terms, possibly even close, to his monarch.

James decided to marry the older daughter and thus became Earl of Moray jure uxuris (by right of his wife). The two married on 31 January 1581 in Fife with much of the nobility of Scotland in attendance, including King James. Afterwards was a huge celebration that included jousting. No doubt James rode at the ring as is mentioned in the song, a form of jousting that takes considerable skill. A jouster gallops full tilt and must put the tip of his lance through small rings. You can easily image this was not an easy thing to do on a galloping horse.

Moray then moved the elaborate celebration to Leith where he set up a large water pageant on the Water of Leith. It culminated with a mock attack on a re-creation he had built of a papal castle. Showing one's anti-Catholic feelings was important in the Scottish court of the very Protestant King James.

|

| King James VI of Scotland (later King James I of England) |

Things seemed to be going along swimmingly for the quite ambitious bonnie young earl. In 1588, he was appointed a commissioner for executing the act against the Spanish armada, and in 1590, was commissioned to execute the acts against the Jesuits. He was, however, at odds with a powerful neighbor, George Gordon, Earl of Huntley, but his favor with the king seemed strong.

So how did it soon go so wrong? The song mentions that 'he was the Queen's true love'. Anne of Denmark and King James were married in 1589 when she was 14 years old. She did acquire a reputation, whether deserved or not, as being flighty and frivolous, but that a 14-year-old queen was given enough freedom to have an affair is highly unlikely. Nonetheless it is possible she showed some preference for him short of an affair. Possible, barely. Would that be enough to explain later events? I am a more than bit skeptical, especially since the Moray's own actions might explain it.

Enter stage left, Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell, one of his wife's cousins, scion of another illegitimate branch of the royal Stewarts. Bothwell had spent several years studying in Catholic nations of Europe and was openly a partisan of the recently executed Mary, Queen of Scots. It is possible in my opinion that he was always a secret Catholic. A quarrelsome man, he was involved in a number of fights and duels, at least one resulting in death.

It would take an entire lengthy blog post to set out his career, but to give the most relevant point, in 1591 Bothwell was accused of practicing witchcraft to call up storms to keep the new queen, Anne of Denmark, from reaching Scotland, which he of course denied. The king, who certainly believed in witchcraft, was furious, so Bothwell was soon an outlaw in hiding. Bothwell led a raid on Holyroodhouse trying to reach the king, probably to plead his cause but several of the king's men were killed. The king and his supporters believed it was an attempted assassination. The king himself led the pursuit of Bothwell which ended with the king being thrown from his horse and having to be rescued.

So this seems like is a very odd time for Moray to make an alliance with the outlaw nobleman, Francis Bothwell. However, Moray's disagreement with Huntley had degenerated into open warfare when Huntley besieged the home of John Grant of Freuchie, one of Moray's allies. Along with the Earl of Atholl, Moray attacked Huntley, broke the siege, and forced Huntley to retreat to Edinburgh.

Huntley had the ear of the king and when the king learned of an apparent alliance between Bothwell and Moray, he gave Huntley a commission to pursue them. Moray was tricked by an associate of Huntley's into believing that the king was willing to hear his arguments in his own defense. He started for Edinburgh. Believing that he would momentarily receive a summons from the king, Moray stopped at Donibristle, one of his formidable mother's estates.

At night, Huntley, who was lurking nearby with a force of his men, attacked the house. He set it afire. Moray did not immediately flee, but eventually he was forced to fight his way through the cordon of Huntley's men. He ran for the rocky shoreline hoping to hide, but the glow of the burning decorations on his helmet gave him away. Huntley pursued him and cut him down.

The next day Moray's mother, Margaret Campbell of Argyll, retrieved her 27-year-old son's body and that of the Sheriff of Moray who had also been killed in the attack. She took them to Edinburgh and confronted King James. He declared that he had not authorised the killings, but took no action against Huntley. She then had her son's hacked body put on display in the Church of St. Giles. The famous vendetta portrait she commissioned displays his many wounds.

|

| Vendetta portrait of the Bonnie Earl of Moray |

Popular opinion, as shown in the ballad, was very much against Huntley who fled to the north, and the king left for Glasgow. Only one of Huntley's followers, a Captain Gordon, was tried and executed. It was no doubt lucky for Huntley that Margaret Campbell died soon after. She would not have been satisfied with the tap on the wrist, not even a slap, that Huntley received which was a week's stay in Blackness Castle until he agreed to give himself up if the king ever had the murder brought to trial.

King James never did.

Saturday, February 17, 2024

William the Rough and the Lion of Scotland

King William I is no doubt best known for adopting Scotland's royal Lion Rampant banner, hence his sobriquet 'the Lion'. He was not called that during his lifetime, however, but rather Garbh, 'the Rough'. His reign definitely had its ups and downs, and whether 'the Lion' is appropriate or not is open to question.

There is no clear evidence when William first used the lion rampant as a banner, but it was in used before his son Alexander inherited the throne. It was Alexander who added the fleur de lis border.

|

| The royal Lion Rampant Banner |

Born in 1142, he was the younger grandson of King David I. His father, Henry, Earl of Huntingdon and Northumbria. Those earldoms were attached to the Scottish crown at the time, gifts from King David's brother-in-Law, England's King Henry I. Earl Henry died when William was ten years old. William inherited the earldoms, a very rich prize indeed, leaving his religious and sickly older brother, Malcolm as heir to the throne of Scotland.

Malcolm inherited from their grandfather in 1153, but soon died in 1165 at the age of 24. Now young William was both King of Scots and Earl of the profitable earldoms of Huntingdon and Northumbria. He granted the earldoms to his younger brother, David (the direct ancestor through his daughter of King Robert the Bruce). William had a perfectly legitimate claim to the earldoms but it so infuriated Henry that even the slightest mention of him threw Henry into one of his infamous furies. William attempted to meet with Henry in 1170 to patch up their badly deteriorated relationship, but Henry refused.

In 1173, three of Henry's sons, Henry (called the Young King), Richard, and Geoffrey along with their mother Eleanor of Aquitaine, rebelled against the king in Normandy which soon spread to England. Since the two kings were on such bad terms, it is not surprising William and his brother decided to join them, leading an army into England, and laying siege to Prudhoe Castle.

Now we come to the 'he may not deserve the sobriquet' part.

King Henry was in Normandy, fighting when the rebellion broke out in England, but he quickly returned. While Henry was in York doing penance for the murder of Thomas Becket quite some time previously, a force of some of Henry's supporters surprised William at night in camp, protected by only a small group of bodyguards. His army was spread out with the siege. William and his men quickly mounted and met the attackers. There is story that King William shouted, "Now we will see who is the better knight!" as he charged impetuously into the fray. Since Henry was not there for him to shout at and it was a surprise attack, I suggest taking the story with a whapping large grain of salt. At any rate, they took him prisoner.

In the aftermath, Henry readily defeated the English rebellion, dragging William about with him and then back to Normandy where he pretty quickly convinced his three sons to surrender and return to his service. In the meantime, he had William in chains in the imposing fortress of Chateau de Falaise. His sons and wife taken care of, Henry sent his army to occupy the southern part of Scotland including its five strongest castles, to which, its king imprisoned and far from his kingdom, Scots put up very little resistance.

|

| Chateau de Falaise, Normandy |

Totally at King Henry's mercy, a man who had no fondness for him at all, after about six months of imprisonment, William agreed to the terms of the Treaty of Falaise. It is hard to say what was the worst part of the treaty. He accepted the English king as Scotland's overlord, agreed for the English to hold the castles they had seized, had to get Henry's permission to put down local rebellions, declared the church in Scotland under the authority of the English, gave up his claim to English earldoms, was forced to agree to send his son to England when he had one, and even had to agree for Henry to choose his own bride. It is difficult to imagine the extent and depth of the humiliation. The personal nature of some of it, such as choosing William's bride, seems to indicate personal hatred on the part of King Henry.

As you can well imagine this caused a lot of problems for William in Scotland and causes later generations to question whether he deserved the nickname of 'the Lion'.

However, now we come to the part where he may deserve the name.

Galloway, Moray and Ross all almost immediately saw uprisings. William and his brother David personally led the response to the rebellion in Easter Ross. The rebellion in the north was put down, started up again and was once more put down. With the aim of enforcing the peace, they built a castle on the Black Isle and another and another at Dunkeath. In the meantime, he had a castle built at Dundee to contain the Galloway rebellion. He was also appealing to the pope to overturn the English control of the church in Scotland. He finally achieved a papal bull overturning that part of the treaty by the pope issuing a bull in 1184.

In July 1189, King Henry II died to be succeeded by his son Richard, later referred to as the Lionheart. And unlike the very hostile King Henry, Richard and William had a good relationship thanks to William having sided with him in the Rebellion of 1173. Richard was also in serious need of money and money was something that William had. (The belief that Scotland was always an indigent nation is false which I will discuss another time)

Richard was eager to leave on his planned crusade, so he was happy to agree to nullify the Treaty of Falaise, including the Scotland's subservience to the English king, for a payment of 10,000 marks. The main issue that remained was the Northumbria earldom that William believed still belonged to Scotland by right, but because William wanted the castles as well as the lands and title, Richard refused to sell it back.

William then led several campaign to Caithness and Southerland in the far north of Scotland, bringing them under the Scottish crown for the first time. He achieved finally putting down rebellion in Galloway and Easter Ross. His other achievements were substantial as well. He increased Scotland's growing trade, largely with the Hanseatic League, clarified Scottish laws, and increased the number of burghs. By the time of his death, had there been made a map of Scotland, it would have been near to the Scotland we see on the map today for the first time in history, not a minor achievement.

William the Lion, whether a lion or not, in my view was a successful king - even with the pretty substantial 'down' part of his reign.

Saturday, January 27, 2024

Scotland and the Knights Templar

First, I apologize for my several months' absence. I won't go

into health issues, but there have been several. Happily, they were not life

threatening but did give me a bit of a kicking. But enough about that. Back to

the Knights Templar...

At the Council of Clermons in 1095, Pope Urban II called for the mobilization of Christians to invade the Levant and retake Jerusalem, which had been held by the Muslims since 638. This began the First Crusade. There was a huge reaction all across Europe. Some entire families joined in the vast army that marched for Constantinople. Much of the crusade was a horrific mess with thousands of crusaders dying of starvation at the siege of Antioch. The culmination was the attack on Jerusalem which combined bizarre fanaticism such as Peter Desiderius claiming to have a vision revealing that if they fasted and then marched barefoot around the city that Jerusalem would fall with interesting medieval strategy and viciousness. Of course, what took the city was when the leaders finally organized a concerted attack, including siege machines. They took Jerusalem in July 1099. Every contemporary chronicle states that the slaughter that followed was of nearly every man, woman, and child in the city. Later historians claim it was exaggerated. I suspect the people who were there knew what happened. And if anyone is astonished that the decades that followed were a quagmire of infighting between royal factions and often murderous intrigue, they need to take a look at the history of Europe.

It was in this state of affairs that the Knights Templar were established in 1118. Hughes de Payen with 8 companions took it upon themselves to found the Poor Fellow Soldiers of Christ and the Temple of Solomon. De Payen proclaimed it their duty to protect the route to Jerusalem for Christian pilgrims. A decade later, they were officially accepted as a religious order. And this is an important point. Many people do not grasp that the Templars were exactly that: a religious order sworn to chastity and obedience. They were even forbidden to enter a home in which there was a woman to avoid temptation. (Always obeyed? Probably not always, but I would not exaggerate that. Certainly, the wild charges worshiping idols, devil worship, spitting on the cross, along with some less improbable homosexuality etc. were mostly nonsense made up by the French king to justify his destruction of the order.)

The Templars were very quickly introduced into Scotland. In 1124 Hughes de Payen visited Scotland and was received by King David I. King David made the Templars welcome, as did all kings across Europe. Their first preceptory, the land probably a gift from King David, was near Midlothian, and called Balantrodoch. A second preceptory was later established and much property across Scotland came into their hands. They certainly had lands in East Lothian, Falkirk, Midlothian and Glasgow. They had some status at the Scottish court as the head of the order in Scotland was the king's almoner (in charge of distributing alms to the poor), but that was not a particularly influential post.

|

| Temple Church, Midlothian |

The head of the Scottish preceptories were English members

of the order, however, that does not mean that all knights at the preceptories

were English. I have seen it claimed that there were no Scottish Knights

Templar, but the idea that the Templars spend nearly two hundred years with a

presence in Scotland and never gained a single member stretches credibility. It

is in fact is false. Their main purpose was recruiting manpower for the defence

of the Holy Land. It would have been a major failure had they not done so.

However, Scotland had a small population so probably there were not many.

In 1302 a Scottish Templar called Richard Scoti was recorded

as visiting the house of the Temple in Paris. In 1309, when Templars in England

were being arrested for trial, one of the Templars arrested was Robert le

Scot. Another Templar, Thomas Scot, managed to flee before he could be seized.

Since only a very few Templar records survive in Scotland, how many others

there may have been is impossible to know. As I mentioned, Scotland's

relatively small population would probably make the number few.

Things changed drastically in 1296. The Knights

Templar in Scotland under their English preceptor claimed they were subject to

the master in England who was subject to the master in France. He in turn was

subject to the master in Cyprus. So when active war broke out between England

and Scotland, the Templars in Scotland along with the Scottish Hospitallers

sided with England.

When in February 1306 Robert the Bruce, soon to be King of Scots, killed John Comyn in the chapel of Greyfriars Monastery, he was promptly excommunicated by the pope. This would of course even further cement the two military orders to the side of the English, but in France charges were already being discussed against the Templars. At first Pope Clement seemed to side with the Templars, dismissing the charges as false which most of them no doubt were. Certainly, King Philip of France was deeply in debt to the Templars. On Friday the 13th, 1307, King Philip ordered the arrest of scores of Templars in Paris. They were tortured and many confessed to the improbable charges. Eventually in November 1307 the pope gave into King Philip's pressure, ordering every king in Europe to arrest all Templars and seize their assets.

However, Robert the Bruce was excommunicated and the kingdom of Scotland under interdict. The pope's writ did not run in Scotland. Scottish bishops had declared that because the pope had been deceived by the English that Scots could ignore the excommunication, which most did. Church life continued as it always had, at least in areas not conquered by the English.

What did that mean for Templars in Scotland? Well, much of

Scotland was in English hands so several, including the English head of the

Scottish preceptory, were arrested and tried in England. No Scots were arrested in Scotland which might mean that there

were no Scottish Templars in Scotland at the time. A more likely explanation to

my mind is that any Scottish Templars took advantage of the fact that Robert the

Bruce was unlikely to arrest them. Although Bishop Lamberton could have held

trials, no trials took place in Scotland.

In the meantime in Europe, especially France, those Templars not yet arrested were fleeing. There have always been rumors, both in Scotland and France, that some went to Scotland where neither the pope nor the French king could lay hands on them. True? It is certainly possible. It would be the only place they could possibly flee.

Might some have fought at the Battle of Bannockburn? This is also a longstanding rumor. Again, that is possible, but they definitely did not fight as a separate division. The divisions that fought on the Scottish side are well known, but some individual Templars could have fought with one of the divisions which were led by King Robert, Edward de Bruce, Thomas Randolph, and and jointly by James Douglas and young Walter Stewart.

In the rest of Europe, the leaders of the Templars met

grisly ends. Grand Master Jacques de Molay retracted the confession that had

been obtained under torture and was burnt at the stake, dying as he rained down

curses on King Philip and Pope Clement. Geoffroi de Charney, Preceptor of Normandy, also repudiated his confession and was burnt at the

stake.

Trials were held all across Europe except in Scotland, however, few former Templars other than their leaders were convicted. Most were eventually released (after a no doubt charming stay in a medieval dungeon) and assimilated into other orders, mainly the Knights Hospitaller.

The Scottish Knights Hospitaller after the Battle of Bannockburn decided they were not nearly as fond of the English as they had thought and shortly came into King Robert's peace. Were some of their members former Templars? I consider that very likely as they took in Templars in other kingdoms as well as receiving the Templar's properties. At any rate, the Hospitallers came to be a powerful presence in Scotland and influential in the Scottish royal court, free of being headed by an English master.

And is there Templar treasure hidden somewhere in Scotland?

While I remain skeptical, it seems that much of the Templar riches were not

accounted for, so it is not impossible.

Tuesday, October 3, 2023

Scotland and the Crusades

Because of the huge interest and emphasis on the centuries of war between England and Scotland, that Scotland was part of the larger community of Europe tends to be overlooked. In fact, Scots were involved in European affairs and Scots took part in the crusades.

The First Crusade was called by Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont in November 1095. There are references to Scots being amongst the crusaders, but no specific names have survived so it is impossible to tell how many or who took part. After the end of that crusade, most crusaders naturally returned home, leaving the captured Jerusalem and lands known at the time as the Levant short of defenders, leading to the foundation of the military orders of the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller.

In 1198, Hugh de Payens, founder and master of the Knights Templar, arrived in Scotland and met with King David I. That meeting went so well, although there are no records of details, that the Scottish King gave the Templars their liberties of Scotland and land for their first Scottish preceptory (the word used for a monastery of the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller) at what is now Temple in Midlothian.

There they built one of their typical eight-sided churches. Unnamed Scottish knights then accompanied him on his unsuccessful attempt to capture Damascus the following year. By 1239 the Templars had founded a second preceptory at what is now Maryculter.

During the Ninth Crusade, led by the future King Edward I of England, we finally have names of Scots who took part led by the Earl of Atholl and included some of the most prominent names in Scottish history. It is a safe assumption that Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller from the Scottish preceptories were there as well. A main responsibility of the knights militant was recruiting members to fight, so without doubt there were at least a few Scottish Templars. The Stewarts and Balliols took part in that crusade. Robert de Bruce, the Competitor, and his son Robert, Lord of Annandale and (through his wife) Earl of Carrick, did as well.

The widely told story that Marjorie of Carrick held him prisoner to force Robert de Bruce (King Robert's father) to marry her when he brought her word of her husband's death at the fall of Acre is certainly apocryphal as they married before that city's fall. However there are clear records that he did take part in the Crusade.

The fall of the Templars came in the middle of the Scottish Wars of Independence and I will write about them and their part in Scotland next time.

After the fall of Acre and the loss of the entire Levant, popes continually called for another crusade, but none happened to recover it. The European nations were too busy fighting each other to mount another crusade to distant lands, but that was not the end of Crusading. Any war against non-Christians or heretics was called a crusade and there again Scots took part.

Thus when James, Lord of Douglas, carried the heart of Robert the Bruce onto the battlefield fighting the Moors in Grenada, he was following his orders to carry it on crusade. He fell in battle near Teba where a monument to him has been erected.

Photograph by Diana Beach.

During periods when Scots could not prove their mettle against the English and there were no more crusades to the Levant, many joined in the Baltic Crusades against Baltic non-Christians. Though rarely discussed, they were every bit as violent and harsh as the crusades in the Levant. The last of the Baltic Crusades was the Teutonic Knights against the Lithuanians which lasted until 1410 in which a number of Scots took part. In 1391 William Douglas, Lord of Nithsdale, illegitimate son of the Earl of Douglas, set off with his companion Robert Stewart of Durisdeer. Douglas was assassinated by the English in Danzig. In gratitude for the efforts of the Douglases, the burgh added the Douglas coat of arms to the High Gate. Such was the end of Scotland's part in crusading.

Friday, September 15, 2023

Just where did the Douglases come from?

By the time of the death of King Robert the Bruce, his great captain, James, the Black Douglas, was one of the most powerful and richest men in Scotland. But even in James' father's time they were neither rich nor particularly powerful, and it is an good question where they came from and how they ended up so powerful they were seen as a threat to the monarch.

Like a great many medieval families, the surname Douglas was originally a place name and title. It came from the river Douglas. In Scots Gaelic 'dubh' means black or dark and glas means grey-green. Near the banks of that river the first of the Douglases known to history, named not surprisingly William of Douglas, built his castle and took the name as a title. But where did he come from?

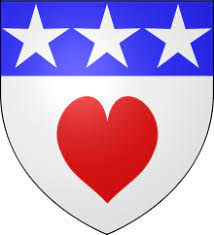

It is notable that the Douglas escutcheon and that of the very important Murrays are nearly identical, three white stars on a blue band. (In heraldry azure, three mullets argent) That has led to speculation that the two families were related, but speculation is not necessary. In 1362 when Archibald the Grim was preparing to marry the Murray heiress, he had to send to the pope for a dispensation because they were related within six generations which confirms that they were related. It is known exactly where the Murrays, or Morays as they were known earlier, came from. They were originally Flemish and fought as mercenaries for King David I in his war to claim the crown of Scotland. He rewarded them with lands and they became an important family in the Scottish court.

I think we can safely conclude that the Douglases were a cadet branch of the Murrays. It is likely that William of Douglas set off to build his own power base. He signed various charters as a witness between 1175 and 1215, so he is firmly placed in history.

However, they had neither their relatives wealth or status, and were not of great significance on the national stage. They worked to build their power base, which was land in medieval Scotland, but little is heard of them. In 1263, William of Douglas, known by the sobriquet 'Longlegs', fought for the Scots at the Battle of Largs, in 1263, a battle between the Norwegian army and the Scots which the young Scottish king Alexander III won. It would surprise many that Scotland was at peace with England but fighting the King of Norway who wanted to claim western Scotland.

It was Longleg's son, yet another William of Douglas referred to as William le Hardi (William the Bold) who began the family's real climb to prominence. In 1270 and still in his twenties, he accompanied David, Earl of Atholl, and many other Scottish nobles on the Eighth Crusade. By 1289, the ambitious young man was styling himself Lord of Douglas, the first time that title was used. He had become important enough to marry Elizabeth Stewart, daughter of the High Stewart of Scotland. She died shortly after giving birth to James of Douglas, probably of complications of child birth.

At about that time King Alexander, after a long and successful reign, died when thrown from his horse.

William le Hardi was not a man to let the grass grow under his feet. Pretty shortly after his first wife's death, he laid siege to Castle Fa'side and kidnapped Eleanor, widow of William de Ferrers, a considerable landowner in both England and Scotland. The Scots arrested him but then released him, and the two were married. She obviously could have escaped his grasp while he was imprisoned so one must make of that what you will. At any rate, King Edward I of England was enraged as usual and demanded that William be turned over to him, a demand the Scottish guardians of the realm chose to ignore.

Sadly the long peace between England and Scotland was rapidly coming to an end. It was the mistake of the Scots to think that they could trust Edward of England. They should have taken his brutal conquest of Wales as an example but did not.

When King Alexander's last direct heir of his body, his granddaughter Margaret, died on her way to Scotland, there was no clear heir to the throne. The Scots asked King Edward to mediate between the several claimants, prominently Robert the Bruce, called the Competitor and grandfather of Scotland's hero king, and John of Comyn. Primogenitor had still only been loosely adopted in Scotland and laws of inheritance in Scotland differed from those in England. Because of later events, it is largely assumed that King Edward decided to declare John the king because he was a weakling. Edward may have believed that. Certainly, in Scottish tradition, which Edward ignored, Robert the Bruce had a better claim. He was closer by one generation to the late king.

Edward lost no time in trying to force King John and the Scots into subservience to him and his rule. He even overturned a ruling by a Scottish court and demanded that King John appear before him in England. John at first gave way, but the Scottish nobles forced him into defiance. Thus began the war. After the disastrous Battle of Dunbar in which thousands of Scots died and hundreds taken prisoner, King Edward stripped King John of the throne of Scotland and declared Scotland his personal possession by conquest.

It did not take long for rebellion to rise. Douglas's cousin in the north of Scotland, Andrew de Moray, son of the Lord of Petty, raised his banner in rebellion while in the south of Scotland, the more renowned William Wallace did the same. William the Hardi promptly joined with Wallace in fighting the English. He was twice taken prisoner. The second time, he died of maltreatment in the Tower of London, but the English had failed to gain possession of William's young son. James of Douglas was safely in France, but he soon joined the household of Bishop Lamberton as a squire.

When Robert the Bruce, Earl of Carrick, raised his banner and seized the throne, young James threw his lot in with the new king.

It was James who earned the title of Black Douglas and fought, side by side, through the long years of struggle and war with King Robert the Bruce. In that was richly rewarded with vast land holdings and powers as they pushed the English out of Scotland. King Robert on his deathbed tasked James with carrying his heart on crusade. James died doing so and ever since the Douglas escutcheon has shown a heart below the three stars.

Only three years after James's death, the English once again invaded Scotland, for a time pretending to do so on behalf of the son of the man they had stripped of the crown. James's only legitimate son, young William, died on the field as a squire to his uncle Archibald. Through forty more horrendous years of fighting, the Douglases led the fight for Scotland's freedom, but with great power and wealth too often comes arrogance. It was unweaning arrogance that was a few decades later their downfall.

Wednesday, August 2, 2023

One of Scotland's great heroines! Part 2

Agnes Reynolds, Countess of Dunbar, must have watched from the ramparts as William Montague, Earl of Salisbury's huge English army surged into view and formed a camp, cutting her off from aid. A woman of only about thirty who had spent most of her life in the midst of a desperate war, she knew what to expect. Of course, that did not prevent her defiance, but she had to wonder how long even her well-provisioned castle with a deep well within its thick walls could hold out. Her husband, Patrick, Earl of Dunbar, and most of the Scottish army were in the north of Scotland.

Three years before under the leadership of Andrew Murray, the Scots had destroyed the army of David de Strathbogie, the chief lieutenant of the English in the north. Now even the walled city of Perth and Stirling Castle were in danger of falling if Salisbury did not lead his army to their relief. But first Dunbar Castle had to be taken.

The construction of trebuchets began. Then they flung massive rocks and even boulders. Day and night, they pounded the castle walls. However, bombarding Dunbar Castle was not an easy task. They could not be brought close enough to do maximum damage despite the size of the stones used. Some of those boulders the canny Agnes ordered saved for her own use.

The crashes of huge stones against the ramparts were constant. So were the taunts from Agnes as she sent her women to dust the castle's crenellations behind which her archers took potshots at the enemy. At one near miss, Salisbury is said to have quipped, "There comes one of my lady's cloak pins. Agnes's love shafts go straight to the heart."

After weeks of frustration at watching little damage from their bombardment, Salisbury ordered the construction of a battering ram, sometimes referred to as a 'sow'. Out of reach of her archers, his men hung the trunk of an ancient pine by chains from a slanted roof mounted on wheels. Fresh cow hides covered the roof.

As the English soldiers heaved beneath the protection of the roof and pushed it closer and closer to the castle's thick wooden gates, her archers shot fire arrows at it. They all sputtered out when they struck the damp hides. If the English broke through the gate, even her strong castle could not hold out. The sow must be destroyed!

There was still one last hope. That hope had been sent her by the English. Her men dragged and hauled the largest of the boulders that had been flung against her walls onto the ramparts above the gate. Agnes ordered them to hold until the sow was immediately beneath the gate and the first blow resounded. Then they shoved it off. It smashed the sow to splinters. The English attackers not killed fled, many falling to arrows from the walls as they ran.

Salisbury knew that there was more than one way to take a castle. Many castles had fallen to treachery. He managed to get word to one of Agnes's guardsmen that he would be well paid for leaving the gate open the following night. The guardsman agreed. He then revealed the plot to Agnes. When Salisbury led the sneak attack, he was also not stupid. He let his men go first. The portcullis crashed down and the earl barely escaped capture and Agnes called down, "Farewell, Montague, I mean for you to sup with me the night."

Salisbury was frustrated beyond words. No progress had been made, the costs were piling up, and the siege needed to end before Scottish winter set in. As it happened Agnes's brother, Thomas, Earl of Moray, had been taken by the English in an ambush three years previously. He was being held in the dungeon of Nottingham Castle, far to the south as they had wanted to take no chances on his being rescued. But needs must, so a message was sent hundreds of miles south and the prisoner dragged in chains to outside Dunbar. A gallows was constructed, a rope placed around Thomas's neck, and Agnes told that if she did not surrender that her brother would hang.

Agnes sent back the message that as her brother had no children that she was his heir. Hang him if you will, she declared, and I will profit. After a few days, Thomas was returned to Nottingham and his dungeon.

By June Dunbar still had not fallen, but supplies were growing desperately low. The eventual enemy of even the strongest castle was starvation. Agnes sneaked word that she needed aid to the one man who might be able to help. She knew she could count on Alexander Ramsay of Dalhousie and she was right. He found a few small boats. With twoscore of his men, he sneaked by night past English ships that guarded the sea approach, reached the seaward gate, and brought ashore fresh supplies. The English saw the resupply effort going on and charged. Ramsay and his men chased the English back to their camp.

Shortly after, on June 10, 1338, Walter Montague, Earl of Salisbury, gave up and retreated to England having done nothing but expend a lot of English gold and make 'Black' Agnes Randolph, Countess of Dunbar, into a heroine of legend. As the ballad puts into Salisbury's mouth, "Came I early or came I late, I found Agnes at the gate!"

(Postscript: I find it amusing that two years later Thomas Randolph was exchanged for that same earl of Salisbury who had himself been taken prisoner.)

Wednesday, July 12, 2023

Let's talk about kilts

Or in the case of my novels, let's not, because medieval Scots did not wear kilts. Yes, like almost everything else in Braveheart, the kilts were wrong. Mel Gibson lied to you. Of course, those kilts were extra wrong since not only did William Wallace not wear one, the one the characters in the movie wore were wrong in size and drape besides that it was the wrong period. Scots, by the way, also had armor and hair combs. *sigh*

Let me clarify the terms used regarding kilts and what they are made of, which are what I use. A plaid was a piece of cloth, usually of a tartan pattern, 4 to 5 yards long and 50 to 60 inches wide. Because of the size of medieval looms, it took 2 pieces of cloth sewn together to make one. It was often used as a cloak cast about the shoulders. It now refers to the small cloth worn over the left shoulder when wearing a small kilt. Tartan is a pattern of stripes running vertically and horizontally, resulting in square grids. (I am not saying it is wrong to use other terms such as plaid for the pattern, but for discussing kilts, I prefer to use the Scottish terms)

The earliest piece of tartan found in Scotland was from the 3rd century AD so they predated the medieval period in Scotland and no doubt tartans were woven. However, they had absolutely no 'clan' association. That was an 18th century invention. It is safe to assume that the colors before that invention were those found in easily made dyes such as yellow from the very common gorse flower, blues from woad, and browns and whites from the natural colors of the wool.

Medieval lowland Scots seem mostly to have worn pretty

much the same clothes as the people of any other western or northern European nation, with

probably some regional variations because of availability. They probably used

plaids as cloaks, or that seems likely. Highlanders wore a knee-length tunic

called a léine which was also worn by the Irish and, of course, over this they

wore a plaid as a cloak.

There are no references at all to Scots wearing kilts

until near the end of the 16th century, when there are descriptions of them

worn by Scottish mercenaries fighting in Ireland. The garment from the

description seems to have been the great kilt or feileadh mor which is what I

think Mel Gibson was trying for in Braveheart. It differed

vastly from the small kilt that is worn today as it has been for several

centuries. They seem to have worn a léine under the great kilt as a shirt. The

tail end of the kilt seems to have often been worn over the shoulder.

How the great kilt was put on is a matter of some disagreement. There are stories that the material was laid out on the floor on top of the belt, the pleats formed by hand, and then the wearer laid down and fastened it around themselves. The problem with this is a practical one. Many homes would not have a room large enough to lay out a cloth 5 yards long, especially without removing the furniture. Another explanation which has no evidence to back it up but sounds practical is that they had loops sewn inside and were drawn up the much as a hoodie can be drawn up. The problem with that, other than the lack of evidence, is that it would really not form pleats. So I honestly do not know and anyone who says they know for sure is being economical with the truth.

The great kilt was amazingly functional. Even in the midst of a Highland winter, that amount of wool cloth would keep you warm. It had enough width to be draped to cover the entire leg and use as a hood to protect the head, but it could also be draped higher so that it did not get wet crossing streams and rivers. Much of the Highlands is marshy moorlands such as Rannoch Moor. If you wore clothing that covered your legs, you would go around with wet clothing. So both the léine with a plaid or a great kilt are practical clothing. Of course, you run into the usual stories about people in earlier periods claiming they were never washed, which is nonsense and would make it extremely uncomfortable to wear. Having clothing full of filth, as well as ticks, etc. was no more comfortable to people in the middle ages and early modern era than they are to us today.

What by far most kilt wearers now wear is a small

kilt. It did not come into use until around the start of the 18th century.

Essentially the small kilt is the bottom half of the great kilt and more

practical if you are wearing it for urban life. However, a small kilt contains

about 8 yards of material so it can be very, very hot in the summer. The separate

piece that goes over the shoulder is also called a plaid.

The other part of the history of the kilt is, of

course, its banning. After the Uprising of 1745, King George II banned the wearing of any

piece of traditional Highland dress, including the kilt, with the purpose of

destroying all traces of Highland culture. The penalties were severe: six

months' imprisonment for the first offense and transportation for the second. The only exceptions were military brigades such as the Black Watch and even they had to immediately take them off when they were not with their brigade. The ban was not lifted until thirty-five years later in 1782, by which time

severe damage had been done to the Highland way of life.

So the kilt has a very interesting history, but not much of it is medieval. I can sincerely promise that you will never find one in one of my medieval novels.

I apologise for the delay in finishing the story the amazing Agnes, Countess of Dunbar and not posting at the first of the month. I have been swamped finishing my latest novel, but I will complete her story in my next post, at the first of August.

Sunday, June 18, 2023

One of Scotland's great heroines! Part 1

We should not be surprised that Agnes Randolph, Countess of Dunbar, often called Black Agnes because of her black hair and dark complexion, was a heroine. She was after all the daughter of one of Scotland's greatest heroes, Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray, companion and nephew of King Robert the Bruce. There were many female heroes in medieval Scotland though, and she was one of them.

There is some doubt when she was born since there is no record of it. Wikipedia says 1314, but I believe that is in error and that she was born four or five years previous to that. At any rate, she was one of four children of Sir Thomas and Isabel Stewart of Bonkyll.

Like all women of noble birth, one of her primary duties was to marry to establish an alliance or increase the family's wealth and power. The Randolphs, whose earldom covered a large swathe of Scotland north of the Firth, did not need more wealth or power. However, Sir Thomas wanted to tie the sometimes-fickle Patrick, 9th Earl of Dunbar more closely to the Scottish cause. After all, while supporting the English, the earl had given shelter to the fleeing King Edward II after the Battle of Bannockburn and aided in his escape to England. Many felt his loyalty was in doubt. Surely Randolph marrying his eldest daughter to him, a man at least three decades her elder, and thus tying him to the royal family would fix his loyalty.

However, imagine her reaction when on 20 July 1332 her father suddenly died on the way to do battle against invading English-supported pretender to the throne of Scotland. Rumor had it, whether true or false, that her father was poisoned by supporters of the English.

With a child king and only, at best, second-rate or very inexperienced commanders left to protect Scotland from the invaders, it was not long before disaster struck at the Battle of Dupplin Moor at which her older brother was killed. A shocking loss of much of her family in a very short time.

Thus began the up and down fortunes of Scotland in the Second War of Scottish Independence. The pretender was chased from Scotland and then returned with a larger army, given him in payment for making Scotland his vassal state, a much larger army. A year later after the equally disastrous Battle of Halidon Hill, Earl Patrick surrendered the city of Berwick-upon-Tweed to the English and switched sides.

No one knows what Lady Agnes thought about this. Her remaining brother was one of the defenders of Scottish independence, after all. However, both her father and King Robert had supported the English in order to live to fight another day. Perhaps she was pragmatic. But her husband attended the Scottish parliament in 1334 which shamefully ceded Berwick, Dunbar, Roxburgh and Edinburgh Castles and all of Scotland's southern counties to England. At the least, it would have been a painful period.

Earl Patrick's reward for switching sides was being forced to rebuilt at his own expense Castle Dunbar, only 20 miles from the English border, which had been slighted (torn down) at the orders of King Robert. It was then garrisoned by the English. Extended by passages onto rocks in the sea, Dunbar Castle had always been a formidable fortress. Now it was even more so. Not surprisingly at first the English garrisoned it and kept it for their but apparently confident that Earl Patrick had truly changed sides, they eventually returned to him.

Image of Dunbar Castle from a painting by Andrew Spratt

By 1335, when he fought on the Scottish side at the Battle of Boroughmuir along with his brother-in-law, the castle had been returned. He was firmly on the side of the Scots where he remained for the rest of his life. I suspect Agnes always had been.

By 1338, the fight for independence was going much better for the Scots. North of the Firth, only Cupar Castle, Stirling Castle and the strongly fortified city of Perth remained in English hands. (Most of southern Scotland still was although under pressure from Scottish guerilla tactics.) Dunbar Castle was the southernmost Scottish castle.

The English had no intention of sitting back and allowing their newly conquered nation to be reclaimed by the Scots. In December of 1337 at King Edward's command, William Montagu, Earl of Salisbury, raised a large army to take relief to the remaining northern strongholds in English hands. First they must take Dunbar Castle which they dare not leave at their back. So on 13 January 1338, he laid siege.

Perhaps Montagu thought because it was held by a woman that taking Dunbar would be an easy task. If so, he was wrong. He demanded the castle's surrender, assuring her that she would be well treated. She had an unequivocal response. The exact words may be apocryphal. The sentiment is not.

Of Scotland's King I haud my house,

I pay him meat and fee,

And I will keep my gude auld house,

while my house will keep me.

And so began the famous siege of Dunbar Castle.

Saturday, June 3, 2023

Did the Normans ever conquer Scotland? Part II

First, I apologise for being a few days late with this post.

I misjudged and was overwhelmed with other commitments. I know better, but that

does not mean I always do better. 🤦♀️

So, back to what is often called the Normanisation of Scotland, which I believe has often been (and still is, at times) exaggerated.

In 1102, King Henry's brother, Robert, Duke of Normandy, disputed Henry's right to the throne of England. They were saved from open war through negotiations by Bishop Flambard. Henry then set out to punish anyone he felt had not been sufficiently loyal during his dispute with his brother and eventually accused his brother of violating their agreement. Normandy slid into chaos. In July 1106, Henry invaded Normandy. At the Battle of Tinchebray, Henry took his brother prisoner and became de facto Duke of Normandy, although he did not use the title. The King of France reacted by raising an army, and Henry was very busy dealing with the threats on the continent.

It was not until Henry returned to England in 1113 that David could claim his Scottish lands. Though there was no open aggression on either side, there is no doubt David had to use threats to do so.

David married Matilda of Huntingdon, daughter and heiress of the Earl of Northumberland, in 1113, with King Henry's approval. That brought with it the extremely rich Honour of Huntingdon, making David a very wealthy and powerful man. He even named their son Henry out of gratitude to the English king. David was also now in a position to gift lands and power to his many young Norman followers, which he he began to do. Even after Queen Matilda died in 1118, David and King Henry remained good friends, and he kept the king's favour.

Then in 1124, Scotland's King Alexander died.

Scotland did not use Norman rules of primogeniture. Other claimants to the throne had as good a claim as David, perhaps even better, the main one being Máel Coluim, David's nephew, son of King Alexander. But David's father had been king, and he had every intention of claiming a throne he considered his. So the other claimants had the choice of accepting him or accepting war with him and with his Norman friends. Máel Coluim chose war.

After two battles, the defeated Máel Coluim retreated into the vastness of the Highlands, and in April or May, David was crowned King of Scots on the Moot Hill in Scone. However, Máel Coluim continued to fight for the throne, and in 1130, Máel Coluim led a general uprising against David, a very serious one. It included David's most powerful vassal, the sub-king of Moray.

This was when David called for the full support of all of his Norman friends. King Henry sent a large army and a large fleet to support him in rooting out the rebels. There were four years of all-out war until Máel Coluim was captured and imprisoned in Roxburgh Castle, after which no more was heard of him. Now David had friends to support and owed them a great debt. He repaid this debt by granting them lands and titles.

What was adopted with considerable enthusiasm was military feudalism. Castle-building, the use of knights as cavalry, and homage and fealty between king and nobles became the norm. These fit well into existing Scottish attitudes and customs. However, despite the enthusiasm, infantry, wielding spears in schiltrons, remained Scotland's main military tactic, demonstrating how the two cultures came to mix. Along with this, of course, were Norman incomers, not as conquerors but as invited members of the society, who quickly married into existing Scottish nobility so that the upper classes soon became largely Scoto-Normans. As one would expect, this led to a multi-lingual society where most nobility spoke Scots and Norman French and, especially in the Highlands, Gaelic.

Thus, it was that in 1296, when commanded to attack Douglasdale by the English king, Robert the Bruce, Earl of Carrick, of both Scottish and Norman heritage, would proclaim before joining the Scottish rebellion, "No man holds his own flesh and blood in hatred, and I am no exception. I must join my own people and the nation in which I was born."

Tuesday, May 16, 2023

Did the Normans ever conquer Scotland? Part I

Short answer: No.

But there is another longer, more complicated answer about how and why so many people of Norman ancestry ended up in Scotland and as Scottish nobility. But first, let us deal with the complicated part.

We have to go back to King Malcolm III, who ruled after King Macbeth. He and his second wife, Margaret of Wessex, daughter of Edgar Ætheling and better known as Saint Margaret of Scotland, were firmly on the throne of Scotland in 1093. Whether or not their marriage was a love match, and there are hints that it might have been, it was a long and seemingly happy one. Malcolm had a son with his first wife, but he and Margaret had seven children.

Then it ended in horrible tragedy.

After some initial hostilities, King Malcolm made a lasting peace treaty with King William, who had recently conquered England. However, when King William died, his son and heir to the English throne, William Rufus, tried to seize Cumbia, which his father had granted to the Scottish king. William gathered his army, including two of his sons, Edward and Edgar, and marched on England. Ambushed by Robert de Mowbray, Earl of Northumbria, the Scots suffered a crushing defeat. King Malcolm and Edward were killed in battle.

Edgar escaped the slaughter to carry the news home to his mother at Edinburgh Castle. Queen Margaret died a few days later of grief.

Shortly after the queen's death, their uncle, Donald III, attacked Edinburgh. He forced the brothers Edgar, Alexander, and David, then 9 years old, into exile, and had himself crowned King of Scots. A civil war ensued (of course, it did 😜). King William Rufus backed Malcolm's son by his first wife, Duncan. That backing included lending him Norman knights. After Duncan was assassinated, he backed Edgar. Tradition, very possibly true, has it that Edgar had Donald blinded and confined to a monastery, and the brothers were able to return to Scotland.

William Rufus was killed in what may have been but probably was not an accident when out hunting in 1100. His brother Henry I immediately seized the throne and married Edgar and David's sister, Matilda. From that point on, David seems to have been mostly in the English court of King Henry I although Edgar had granted him substantial lands below the Forth.

David may have already been childhood friends with Norman knights such as Robert de Brus, Hugh de Morville, and Walter Fitzalan. But they were no longer children, and those friendships would eventually change the fate of both Scotland and England forever.

That is only the start. I'll write about what happened then next time.

Monday, April 17, 2023

So who was Macbeth really?

Thanks to Shakespeare, Macbeth is one of the better-known of

the early kings of Scotland - or Alba as it was then known. Supposedly, he was

a murderous regicide influenced by witchy hags, who quickly met his deserved fate.

Well... that was Shakespeare's story and a good one at that.

Mac Betha's overlord was Malcolm II, King of Alba, and then his second-in-command and successor, King Duncan I. An important thing to know about royal succession in the Kingdom of Alba is that it was by tanistry, inheritance by the second-in-command, not by primogenitor. For a while, things went all right for King Duncan until, in 1039, he was attacked by the Northumbrians. When he led a retaliatory attack against Durham, it was a total disaster that he barely escaped with his life. In medieval times, a king who could not win battles rarely remained king long.

The next year, Mac Bethad took advantage of King Duncan's weakened position to raid Duncan's lands. Duncan led a retaliatory raid into Moray, where he met Mac Bethad in the Battle of Bothagowan near what is now Elgin. He was killed in battle on 14 August 1040. Duncan's two sons fled, but there is considerable debate about where they fled to.

Although there was no immediate opposition, Duncan's father and brother were killed in battle against the army of Alba in 1045. Otherwise, matters in the kingdom were peaceful, with no opposition to Mac Bethad's rule within Scotland. In 1050, his kingdom was so peaceful that he took a year to travel to Rome, where he scattered coins to the poor as though they were grains of seed. His marriage may not have been so successful since he and Gruoch had no children. He named his adopted son Lulach as his successor, violating the laws of tanistry.

He returned to a Scotland no longer peaceful. Thorfinn Sigurdsson, Jarl of Orkney, pillaged and burned as far as Fife. Since Mac Bethad survived as king, it is safe to say he pushed back Thorfinn's invasion.

However, only a short time later, in 1052, Siward, Earl of Northumberland, invaded Alba with a large army. He met Mac Bethad's army in a bloody battle. There were tremendous deaths on both sides, including Siward's sons and son-in-law, but they still restored the man the English preferred to the throne of Strathclyde. This was a severe blow to Mac Bethad's prestige, but he was still largely admired. He was still referred to as "Mac Bethad the renowned."

But having lost once, he was on a rapid downward slide. After all, having ruled for seventeen years. He was no longer a young man at the height of his battle strength. The eldest son of King Duncan I (remember Mac Bethad killing him?) Malcolm III, Maol Chaluim mac Dhonnchaidh, continued the invasion after Siward's death and killed Mac Bethad in battle at Lumphanan in August 1057.

Poor King Lulach, given the sobriquet the Feeble Minded, was crowned but survived only a few months. His coronation was against the rules of tanistry, so whether his assassination by Malcolm III was unlawful might be open to question. But certainly, Malcolm was no innocent child who had been deprived of his throne by murder. And it is beyond question that Mac Bethad or Macbeth was no tyrant.

So why did Shakespeare claim that Macbeth was a tyrant who only ruled for a short time? Because King James I of England (King James VI of Scotland) traced his ancestry to Malcolm III. It was good, old-fashioned political propaganda done by one of the world's greatest authors. Successful propaganda is when, hundreds of years later, people still believe the lies.