Someone recently put it to me that Robert the Bruce and his captains were fighting for power, not for freedom. He commented that it was just something that Gibson put in Braveheart. Considering that Gibson got almost nothing right about William Wallace, Robert the Bruce, or the start of the Wars of Scottish Independence, I can understand that skepticism. Certainly, William Wallace did not go around screaming "Freedom!" while wearing blue face paint. But is it just possible that they were fighting for freedom? And if so, what did they mean by 'freedom'? (For that matter, what do we mean by it?)

Well there were certainly mentions of freedom in the writings of the time. The first I am aware of was in the Declaration of Arbroath written in 1320. The word is part of the most famous paragraph of that historic letter, written to Pope John XXII and signed by eight earls and forty barons. It made a profound argument for the recognition of Scotland's independence from English rule and Robert the Bruce as Scotland's lawful king.

It was written in Church Latin, as one would expect in a document to be presented to the pope, and contained one of the most quoted sentences in Scotland's history.

Non enim propter gloriam, diuicias aut honores pugnamus set propter libertatem solummodo quam Nemo bonus nisi simul cum vita amittit.

Translated into English, it reads: It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom, for that alone which no honest man gives up but with life itself.

There are other 14th century references to freedom.

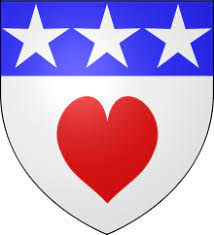

Freedom is mentioned a number of times in the iconic narrative poem The Brus written by Johne Barbour in 1370 about four decades after King Roberts' death, when some of his followers were still alive and had spoken with Barbour, as he actually mentions in the poem. One of the best known references from Barbour's work is on a plaque over where the king's heart is buried in Melrose Abbey. The plaque entwines a carving of a heart (which you also see on the Douglas coat of arms) with a Saltire, Scotland's national flag.

In the original Early Scots it reads: "A noble hart may have no ease, gif freedom failye."

Translated, this reads: "A noble heart shall have no ease if freedom fails."

However, that is only one line of Johne Barbour's paean to freedom.

Because of its length I will only include my own translation into English, but you can find it in the original Early Scots here.

Ah! Freedom is a noble thing.

Freedom gives man happiness,

Freedom all solace to man gives.

He lives at ease who freely lives.

A noble heart may have no ease,

Nor nought that may him please,

If freedom fail; for freedom to please oneself

Is loved above all other things.

No, he who has ever lived free

Can not well perceive the nature,

The affliction, no, the miserable woe

That is coupled to foul servitude.

But if he had put it to the proof

Then he would learn it all by heart,

And would think freedom more to prize

Than all the gold in the world there is.

(This translation is my own work, so any errors are totally on me. If you believe you have a correction, please let me know.)

Thus, Barbour expressed pretty clearly what he thought freedom was, at least in part, the ability to please oneself or do as one pleases, although he certainly also believed in duty to lord and monarch. Probably like most of us who have duty to family and bosses as well as nations to which we are loyal, he and other medieval Scots had a somewhat confused definition of the word. But whatever they believed it was, freedom was a concept many must have fought and died for.